Last week, ACVP blog's analysis of heart disease as a medical mystery left our readers with a few big questions.

Despite all the research and measurement into heart disease on a national and global scale - are we any closer to satisfying answers about how best to continue to decrease heart disease mortality rates?

The history of the heart disease decline - and all the research that came out of it - still might leave us (surprisingly) lost for hard answers.

Attribution of causes, historically, a murky process

In 2013, medical historians David S. Jones, MD, PhD of Harvard Medical School and Jeremy A. Greene, MD, PhD of Johns Hopkins School of Medicine published a history of the decline of heart disease mortality in the American Journal of Public Health.

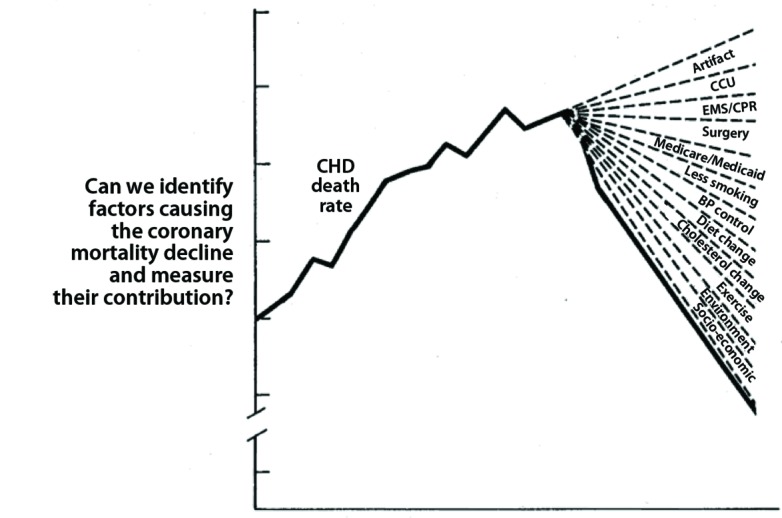

Following their peak in the early 1960s, heart disease mortality rates shockingly declined 20 percent between 1968 and 1978---a decline so large and without simple explanation that a conference was called to determine whether the decline was "real." (It was.)

"Quite simply, the problem was that too many things had changed," write Jones and Greene.

"The onset of decline in the 1960s had coincided with vigorous efforts to educate Americans about smoking, diet, and other CHD risk factors; with changes in medical care, including aggressive control of hypertension, coronary care units, and bypass surgery, and with the passage of Medicare and Medicaid." Jones and Greene, 2013.

Following the conference, researchers went to work on another question - had prevention reduced the incidence of heart disease or had medical care improved the survival of patients who developed it? But further uncertainty led to worry that "their initial assumptions may have been too simplistic."

"Health care and prevention could each influence both event and case fatality rates, making it difficult to distinguish their relative impact," write Jones and Greene. "Decades of surveillance programs did not resolve debates about the causes of the decline."

In the research community, "surveillance" gave way to "modelling," which, with a few simplifications and reasonable assumptions, could assign percentages of impact to different interventions or changes.

But models weren't so foolproof as to end debate on the heart disease decline. "Models, like surveillance programs, have certain limitations," write Jones and Greene.

Limitations of "Modeling:"

- Use simplifying assumptions

- Often use different endpoints which substantially change how models allocate credit

- Incorporate quantifiable and measured factors only

- Generally share credit, without guidance for resource allocation

- Project trends into the future - "often a suspect science"

The purpose of assigning quantifiable percentages would seemingly be to allocate resources efficiently to particular interventions or programs---should more money go to prevention or medical care innovations?---for example. But the limitations of modelling prevent researchers from offering guidance.

Finally, because the models have generally shared credit between risk factor reduction and medical care—a finding that might be both accurate and expedient—they have not provided guidance to policymakers facing difficult choices about resource allocation. The analyses often end like the Caucus Race in Alice in Wonderland, in which the Dodo Bird, officiating, declared that “everybody has won, and all must have prizes.” Jones and Greene, 2013.

It seems as if we aren't much further along than we were when the first big decline in heart disease occurred---then, too many things had changed; now, too many things have been modeled. And still, you might hear arguments that certain things might have a significant effect that simply can't be quantified, measured, or modeled.

Mystifying case studies in global heart disease

Between 1990 and 1994 in Russia, increases in mortality from heart disease and stroke occurred rapidly and drastically. "In a striking echo of earlier explanations of decline, there was not shortage of possible causes for the new increase," write Jones and Greene.

And while "an economic disruption fueled resurgent CHD in Russia," heart disease mortality increased dramatically in China as well, with opposite economic indicators.

"Chinese researchers had described low rates of CHD at the 1988 workshop in spite of high rates of smoking---a finding attributed to the extraordinary qualities of a Chinese diet traditionally low in saturated fat and cholesterol," write Jones and Greene.

But the narrative from China suggests that economic success brought with it an "increasingly 'Western' diet," with heart disease mortality increasing by 50 percent in men between 1984 and 1999 and jumping another 40 percent by 2010.

And despite both cases where Russia and China were significantly affected by cultural and economic change, socioeconomic factors rarely play a role in hear disease public health modeling or research, "because neither the surveillance programs nor the epidemiological models generated the data that would have been needed for these factors to become serious players," write Jones and Greene.

Where are we now?

Last week, we quoted a recent paper in JAMA Cardiology that stated, "The rates of decline of all CVD, HD, and stroke decelerated dramatically between 2011 and 2014."

For an explanation, the paper suggested that prevention programs might be reaching "saturation" in the community, while the prevalence of obesity and diabetes might begin to push heart disease mortality rates to increase.

While the deceleration might have been dramatic, would it be dramatic of us to worry much about it? After all, say Jones and Greene, "The concern over a slowed or plateaued decline of CHD mortality rates remains a blip in the overall trajectory of dramatic and continuing decline in CHD."

Truly, when you think of the sheer number of significant factors that have contributed to such a large and sustained decrease in heart disease mortality rates since the 1960s, you wonder if even an obesity "epidemic" could cause health care to lose much ground on heart disease---especially considering we hear about new best practices and innovations in cardiovascular medicine seemingly every day.

Maybe the new bioresorbable stent approved by the FDA will fulfill the technology's potential and result in much better long-term outcomes for patients, etc.

But what do you think? Should we be worried about a reversal in heart disease? Or will heart disease mortality rates keep falling? Leave a comment!